If you’re a budding videographer or cinematographer, you’ll no doubt have heard the word ‘anamorphic’ tossed around when discussing certain lenses. You know that it can give you those long, J.J. Abrams-style light flares, but what else are they good for? How are they different from other lenses?

The Basics

With an alternate design that features a front or rear glass element that’s more cylindrical than spherical, anamorphic lenses compress or squeeze your image horizontally before it hits the image sensor or film plane. If you want to achieve a normal look with an anamorphic lens, you’re going to have to take an extra step in the editing process and stretch or de-squeeze your images.

When desqueezed and resized, the above image straight out of camera turns into the below image.

Sirui‘s recent batch of newly-produced (and affordable!) anamorphic prime lenses for APS-C sensors squeeze your image horizontally by a factor of 1.33x. This allows you to get a 16:9 widescreen look from a 4:3 image sensor. If you want to stretch even further, this gives you the opportunity to get an ultra-cinematic 2.39:1 aspect ratio from a standard 16:9 image.

Still a little confused? Check this out.

The Technical

When anamorphic lenses first broke onto the cinema scene, they allowed a director to fit more of the wide-sweeping scenery onto a single frame. This was great for the cinema, since home televisions at the time were only offered in a boxy 4:3 aspect ratio. The widescreen 16:9 or 2.39:1 aspect ratio gave moviegoers something special in the form of a vast, sweeping landscape that they could only witness in the theater.

Modern times and the advent of digital has seemingly introduced us to even more aspect ratios than ever before. Technically, there’s nothing stopping a photographer or filmmaker from cropping to any size or image ratio they desire.

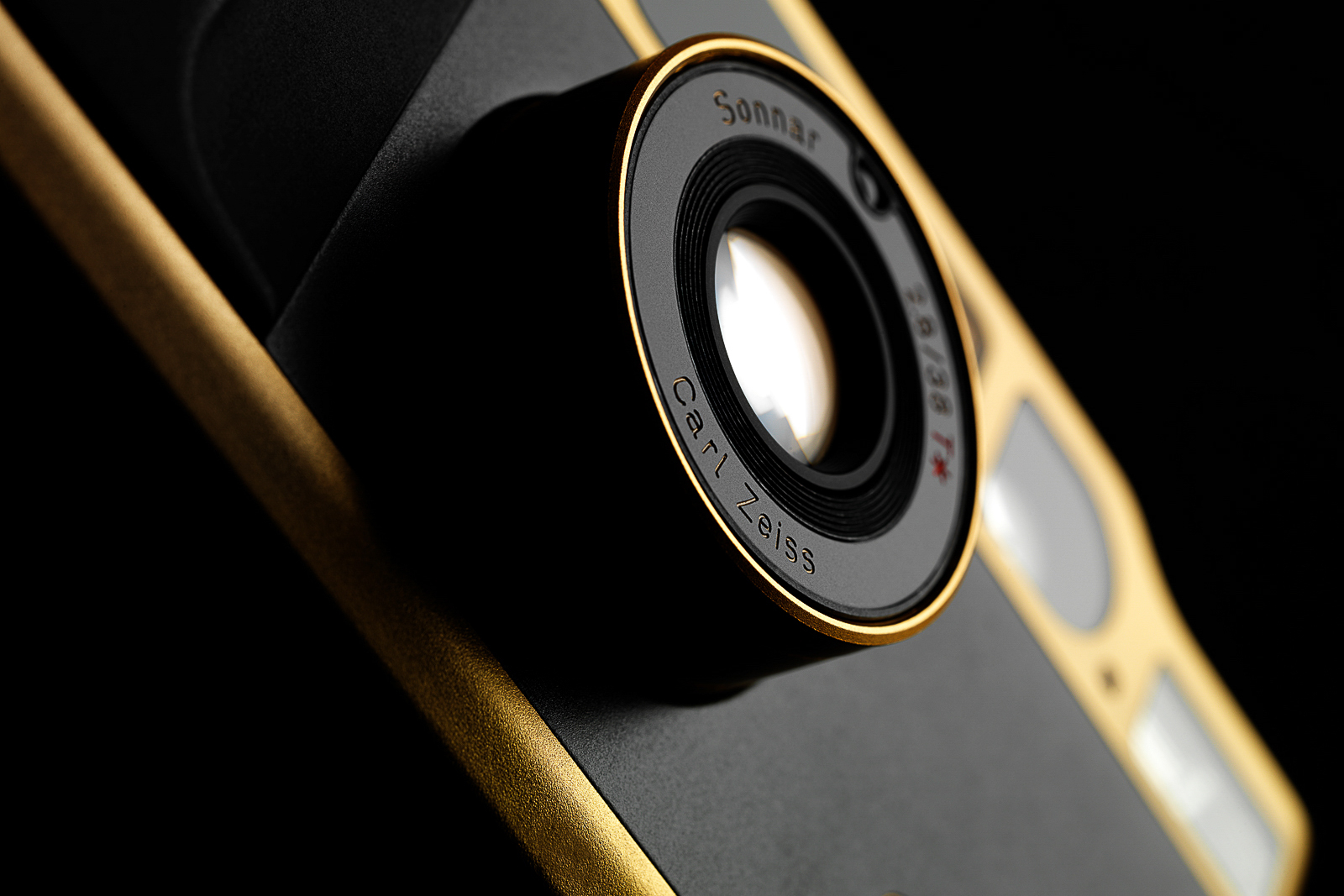

So why wouldn’t a modern filmmaker simply shoot in 16:9 and then crop to 2.39:1? Many creators do just that– filming at a wide focal length with Zeiss Compact Prime lenses and cropping the frame to their desired aspect ratio.

However, this method doesn’t fully utilize the image sensor, meaning you’re dropping resolution and essentially trashing a portion of your image. With today’s 6K sensors, this hardly seems worth noting, but take the following for example.

If you’re shooting a scene in 4K UHD resolution, you’re getting 3840 horizontal by 2160 vertical pixels. This gives you a total of 12,746,752 pixels in a standard 16:9 aspect ratio. By cropping out the top and bottom portions of that to make it a 2.39:1 aspect ratio, you keep the width but lose vertical resolution. You’d be cutting out 552 vertical lines of resolution, disregarding more than a quarter of the image you shot.

Instead, you could shoot your scene in 4K UHD resolution using a 1.33x anamorphic lens to compress more image onto your sensor and desqueeze the image in postproduction to 2.39:1, keeping all of your sensor’s information and simply adjusting how the viewer sees that info.

The Creative

Let’s say you aren’t a pixel peeper and–considering that most media is watched on small smart devices than in the theater–don’t really care that much about resolution and pixels.

An anamorphic lens will give your image a few defining characteristics that are easily identifiable when compared to a spherical lens. Due to the nature of the design, the edges of the frame tend to distort and blur more often than you’d see in a spherical lens,. Here, the center of the image is almost always clearer than the corners.

There’s the iconic blue streak flare which makes for excellent sci-fi and futuristic looks.

Most bokeh will transform from round to oval-shaped as well. The Sirui lens tested here offers a bit of that ‘swirl’ bokeh found in some other classic lenses as well.

Additionally, anamorphic lenses tend to have a kind of cinematic quality that can be hard to describe. It could be that, due to most modern-day lenses striving to be optically perfect, the introduction of stylistic aberrations and imperfections make an image look more natural and pleasing.